A flower was offerd to me;

Such a flower as May never bore.

But I said I’ve a Pretty Rose-tree,

And passed the sweet flower o’er.

Then I went to my Pretty Rose-tree;

To tend her by day and by night.

But my Rose turnd away with jealousy:

And her thorns were my only delight.

In Part One, we had just completed our discussion of the first stanza:

Maybe he’s lulling us into a false sense of complacency. I hope so. Anyway, so much for the first stanza. The second one begins like this:

“Then I went to my Pretty Rose-tree”

|

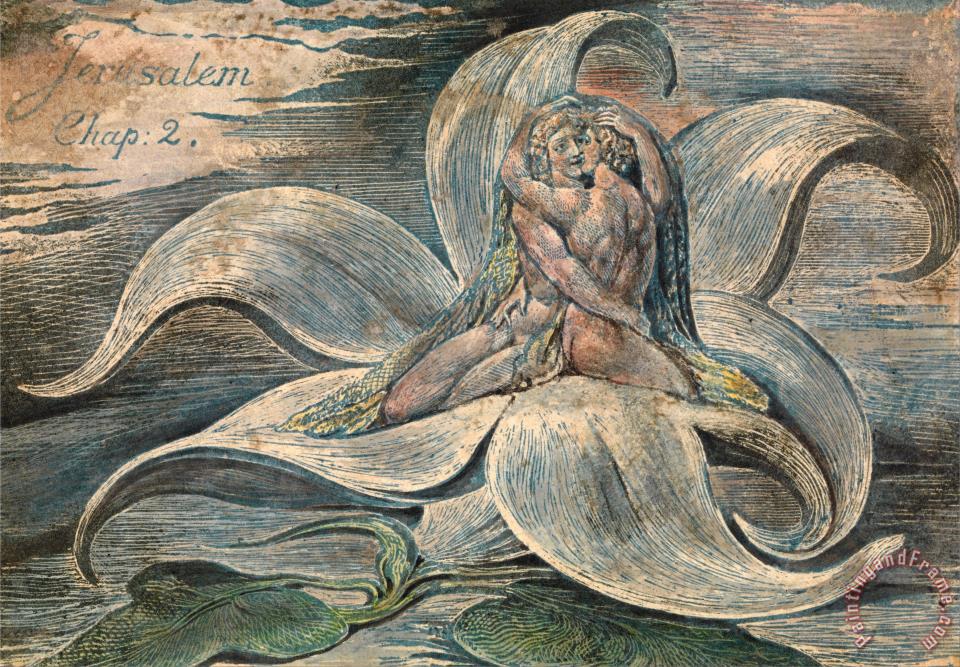

| From Blake's unreadable epic, "Jerusalem" |

Does anyone notice anything about the sound of this line? A repetition? It’s a little subtle, but it’s there. No? Just read the first three words: “Then I went.”

Mortimer: Do "then" and "went" rhyme?”

Almost. The “eh” sound is repeated, and we hear it again in “pretty.” Repetition of the vowel sound is called assonance, in case Fanyone asks. Does this assonance matter? Does it accomplish anything? Is there a “so what” to it?

Let’s look at these three words one at a time. “Then” defines the relationship between the narrator’s passing over the sweet flower and his going to his pretty rose tree. It can refer to time – at that time, immediately afterwards, at the same time – or a causal relationship – in that case or consequently.

“Went” describes his movement toward his rose tree. What does it look like to “went”? Can someone “went” for us? It’s not very descriptive, is it? And if it’s not descriptive, it’s hard to determine any strong emotions associated with the movement. What are some positive words Blake could’ve used to make his rose tree and his writing teacher happier?

Adler: Hurried.

Rumpole: Raced.

|

| Blake doesn't like this guy |

Fagin: Hastened.

Penny Lope: Sprinted.

Elmira: Skipped.

Enough! The poet passes up an opportunity to show how much the rose tree meant to the narrator. If you’re in a relationship, you don’t want your special someone to “went” to you, do you? I didn’t think so. Okay, how about “pretty”? Does that help?

Eudora: No, because he’s already used that, and he chooses not to upgrade it to gorgeous or whatever.

True. He adds nothing to his description. He isn’t moved to elaborate on whatever special qualities that called him away from the sweet flower that May never bore. So why is he going back?

Teddy: It’s the right thing to do.

Well put, Teddy. Next line:

“To tend her by day and by night”

|

| Painting by Blake. Discuss in context of "Rose Tree" |

Maudie: I think it could be ‘tend,’ because it sounds like ‘then’ and ‘went.’”

Does that sound right to everyone? If Maudie’s right, we should expect ‘tend’ to be as un-uplifting as those other two words. What associations do you have with the word ‘tend’?

Maudie: You have to tend gardens, and that works here because "she" is a rose tree.

Great. And rose gardens tend to require a lot of tending (pun goes unappreciated). Anyone else?

Jody: You tend sick people.

Meaning . . .

Jody: You take care of them, look after them, bring'em something to eat, change their bedpa--

Fine, that's enough. The narrator goes to his pretty rose tree to look after her the way he would a garden or a sick person.

Jody: But you could also say he’s returning to tend to the relationship. My youth minister said a relationship will weaken and grow dull if you don’t work at it every day.

Good addition – my thanks to your youth minister. Now let’s look at the last part of the line: “by day and by night.” Does anyone know the name for the way these words are arranged? I know you’ve seen it before; you see it all the time.

Jody: Repetition?

Well, yes, but I’m looking for another name. Starts with the letter “p,” second letter “a,” . . .

Maudie: Parallelism!

Exactly. But does it matter that these words are in parallel structure? Finish the sentence: Blake’s parallel structure in line 6 creates or evokes _________.

Medea: A sense of commitment. He’s there for her 24/7.

Jason: A feeling that she’s high maintenance. There’s always something else he has to do for her. And it’s like Jody said to start with – it’s repetitive, boring.

I’m hearing you say, as a group, it could be good, it could be bad. But imagine the rose tree overhearing this. Wouldn’t she wish he’d said something more? For example, “I'm sorry, Flower May Never Bore, but once you find the love of your life you can’t live without her. I would never consider leaving Pretty Rose-Tree. I’ll now fly back to her post haste and stay by her side every minute of every day!” Something like that.

Let’s suppose the poem ended here. Is there a moral? Has the narrator done the right thing? Will Blake have taught us something with these six lines?

Medea: To be faithful to your spouse.

Erica: To honor your commitments.

Maudie: To avoid temptation.

Didn’t we already know these things? If so, the poem’s just sort of a booster, a reminder. “So, dear reader, as you’ve been told since time immemorial, be faithful to your spouse and honor your commitments.”

Erica: Is it wrong for a poet to simply illustrate a moral choice in action?

I don’t think so. But in my experience it’s not typical for a great poet to “simply” anything. They tend to enjoy complexifying things.

Jody: You said earlier the rhyme scheme was simple and predictable. Maybe his message is, too.

Good point. You’re making me nervous, because I hate to be wrong or to have my expectations unfulfilled. This poem’s not over yet. Before we look at the next line, quickly jot down what you think will happen next.

Roughly five minutes later . . .

Okay, here we go. Let’s see if you nailed it:

“But my Rose turnd away with jealousy”

Holy Moly! You didn’t see that coming, did you? Why isn’t she happy to see him?

|

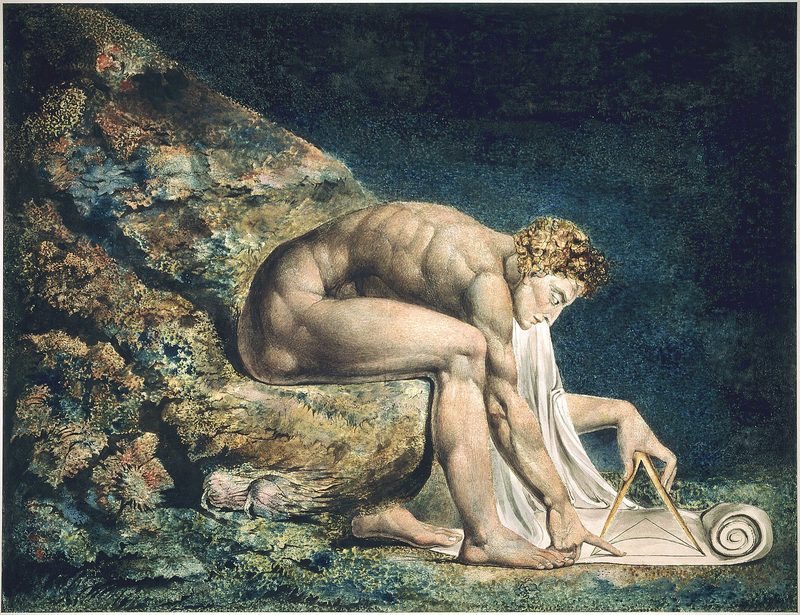

| Blake's painting of a scientist. Can you name him? |

I guess you could infer that, but it’s not in the poem. Her jealousy seems to be coming out of something unspoken, something in the air. Maybe she knows she’s being tended to, but not adored. She knows he “went” instead of hastened, and that makes her jealous, because surely there is something or someone for whom his feelings would be more than obligatory.

Does the narrator get anything for passing up the offer of a flower that May never bore? Let’s see the last line:

“And her thorns were my only delight.”

(Groans, “whoas,” and a general uneasy stirring in the classroom.)

I agree. What word in the line is making you respond this way? Which one cries out for our attention?

Jody: "Delight," obviously.

This creates a tone issue, don’t you think? He either really does get delight (i.e., joy, great pleasure, rapture) from her rejection or he is being ironic and saying the opposite of what he really means. Which is it, or is it something in between?

Wilborn: I think he does get delight from her thorns. The fact that she’s jealous and turns away from him means she still feels something for him. That makes him believe he’s done the right thing and his sacrifice was worth it.

Maudie: No, I think it’s sarcasm. "I pass over this hot and sensual Beyonce woman and all I get are accusations and rejection. I do the right thing and I get nothing in return.”

Jethro: Maybe he’s a masochist and he likes pain, and she’s got the whole thorn thing going, so for him that would be delightful.

Adler: Maybe he was expecting a little something else, but wound up having to go to bed "thorny."

Whoa! I think that’s enough. So some believe his “delight” is that she still cares, others think it’s a case of virtue going unrewarded. And Jethro here thinks it’s an S&M relationship, but I’d have to look carefully at all the poem’s earlier lines to see if there’s sufficient evidence to make a case for that.

For a second, though, let’s ponder the virtue issue. Are we completely certain that the narrator did “the right thing”? It’s hard to argue against the virtue of committing to another human being, especially a marriage vow. But no one has argued that the narrator’s fidelity or loyalty has made anyone happy or improved anyone’s life – unless he actually does receive delight from her thorns.

Maudie: Whoever said we're entitled to be happy?

I see you've been reading Thomas Carlyle again, Maudie. "Happiness entitlement" could definitely be an issue here.

At any rate, there’s something about his coming back that doesn’t make the rose tree happy. There is no joy in the narrator’s decision to remain faithful. He uses his most positive language to describe the flower, while his praise for the rose tree is lukewarm at best.

Can our effort to do the right thing, then, be tainted by our motives? Are there times – only after our teen years, obviously – when impulse should override duty?

Blake knows that his late 18th-century audience and even the majority of 21st-century AP Lit students would create a simple dichotomy between commitment and betrayal, or love and lust or, more generally, right and wrong and good and evil. His poem seems to encourage that view, in a way, with its simple structure and that ABAB rhyme scheme we referred to earlier.

But like all good poetry, it leaves us with more questions than answers: “Goodness wasn’t rewarded. Why not? And what is goodness, anyway?” It has illustrated a problem without trying to solve it. Anton Chekhov, the Russian playwright and greatest short-story writer ever, said the writer’s job was to simply (that word again!) truthfully and accurately articulate the question, not to answer it.

We said earlier the flower and the rose tree may symbolize two women who may in turn symbolize other choices. Years ago one of my students – let’s just call her “Julie Ashby” to protect her anonymity – wrote an essay on this poem in which she saw the rose tree as a symbol for the known, what we have, or what is guaranteed. (If you've read French Lieutenant's Woman, think Ernestina Freeman and Sarah Woodruff.)

In Julie's essay, the flower symbolized the mysterious, the Faery's Child, potential, Desire with a capital D, the risk, the maybe . . . a choice one makes at the expense of what one already has.

In her personal interpretation, the rose tree was a career in her father’s marketing firm. He paid for her college tuition, in fact, with the understanding that regardless of her studies there, she would return to join his business.

The flower that May never bore, on the other hand, was the temptation to became a major in English, a discipline that had begun to seduce her when she was an impressionable sophomore. This illicit relationship continued through her senior year at which time she wrote her essay on Blake’s poem, concluding with a declaration of her independence from her father and his worldly offer in favor of the Siren with her countless alluring songs, Literature.*

Wilborn: So Blake's saying the flower isn't a skank? He's taking the side of temptation?**

Good question. I have no idea. Read it carefully a couple more times and see what you think. You guys be careful, have a good weekend, and thanks for coming to high school today.

*Full disclosure: Julie changed her mind later.

**Fuller disclosure: In fairness to Wilborn, Blake did write this: "Why should I be bound to thee / O my lovely Myrtle-tree? / Love, free love, cannot be bound / To any tree that grows on ground."

It would be interesting to know if “eh” had the same meaning In Blake’s day as it does today, as in: “Did you like that new signature panini place?” “Eh.”

ReplyDeleteSort of, I think it did.

Delete