I was stationed near Fukuoka on the northern part of Japan's southernmost island, Kyushu. What an exotic place! Almost immediately I learned that the "Local Nationals," i.e., the Mama Sans, i.e., the barrack-cleaning Japanese ladies would walk right into the john while you were doing your business, and make smart remarks in broken English, to which you responded as if you were talking to children.

My first afternoon, some guys from my barrack took me to explore nearby Hakata where I learned that Kirin was Japan's Budweiser -- cheap, popular and not all that good -- and I plucked one from a cooler like the ones I used to see in front of gas stations, and took a sip: It was a little too warm, but it tasted like beer, so I drank it.

Oh, the beauty of diversity on this great planet! The joy of seeing how the other half lives!

Even God was different here.He did not seem to scrutinize Japan as severely as He did the Baptist churches in Pinetta and Pine Grove and the woods and pastures surrounding them. I had gone through all the days of my life with the Big Guy looking over my shoulder, staring at me like the vulture eye from "Tell-Tale Heart," marking demerits, counting and classifying whatever sins I committed, a Cosmic Santa Claus with an attitude and with punishment a hell of a lot worse than a bag of coal and a bundle of twigs.

This intrusive omniscient gaze was cultivated and nurtured in my youth by a culture of snug conformity. The little chunk of north Florida dirt that spawned me could be called, with little exaggeration, God's Little Acre. Our world was so small, so homogeneous, that to read our neighbors' minds we needed only to read our own.

We lived bound by soft chains protecting us from difference, from the Other. Those chains made us a community, and the community kept us from being alone. The chains kept us comfortably in the Garden, kept the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil hidden, and allowed us to see the multifarious world through only a single, limiting lens.

I'm not complaining. I like simplicity, even if I mistrust it. For the most part, I enjoyed living in a brooding pen. It never occurred to me then that I would ever leave it.

In Japan, thank God, the Divine Gaze either faded or my awareness of it did. After all, this was Buddha's territory, and he had no reason to care about me one way or the other. I was free to have what Kurt Vonnegut called a "non-epiphany," a phenomenon that allows one to "contentedly drift in the cosmos . . ., that rarest of moments, when God Almighty lets go of the scruff of your neck and lets you be human for a little while."

I wasn't the only one who felt this way. I would often bike or ride through the countryside with a friend who had a similar upbringing, and he would say, "There's Buddha's field" or "That's Buddha's rice paddy," and "Look at Buddha's big blue sky!"

My neighbor, an American sailor's wife, would do that, too, when she was drunk. She would weep and talk about how her husband didn't love her enough, then look up at the sky and wail, "Oh God, look at Buddha's moon. And look at Buddha's stars!" Then she would snort out a laugh and go back to crying about her husband.

There was another element that facilitated my release from what Flannery O'Connor called my Christ-haunted roots: As someone forced into the Air Force because of the draft, I became a member of a large and cranky fraternity, one not likely to be confused with the Body of Christ. We weren't like college guys who actually wanted to go through a fraternal dress rehearsal for corporate bullying, but we still had the hazing (read about it here) and the chummy (read "claustrophobic") living conditions with our fellows.

We were angry young men, as young men tend to be when forced into, say, four years of a life they loathe, a life of obedience to men they don't respect and of unrelenting submission to lunacy on an epic scale.

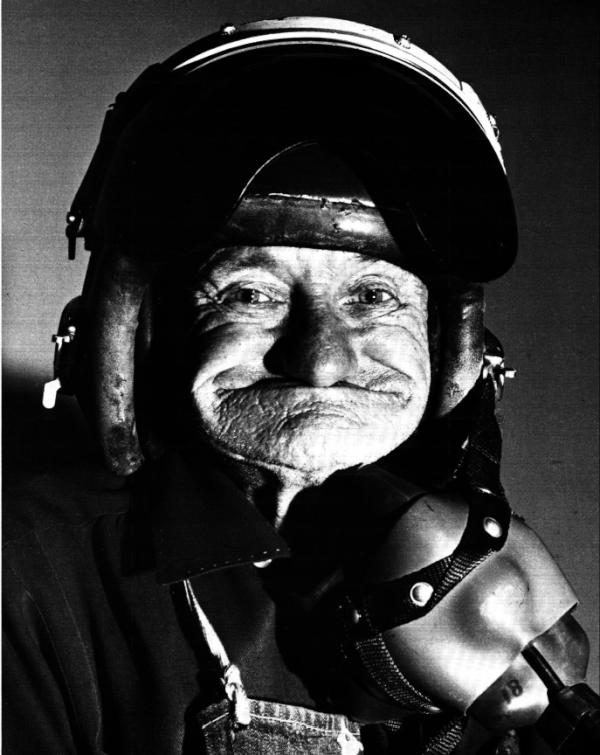

|

| 1970 caption: "Sleep well, America! Your Air Force is." |

Our anger was exacerbated by our being children of the Sixties. We were supposed to be back home occupying some dorky college administrator's office or marching and chanting in protest of the very war we were supporting. Thus, many of us saw ourselves as cowardly hypocrites.

We didn't think our lot would be improved by going to chapel. Hell, the chaplain was an officer, and we could see the sissy do-gooder riding around the base with the real officers (called "pukes" and "pricks" by the non-commissioned), the ones who delighted in reminding us not that we were the salt of the earth, but that we were low-life maggots who were not getting paid to think.

God's servants were on their side, supporting The Mission we mocked with our every breath.

We already knew God would not answer the prayers we sent His way. For about 90% of us, just our being in the Air Force was proof he was deaf to our greatest desire.

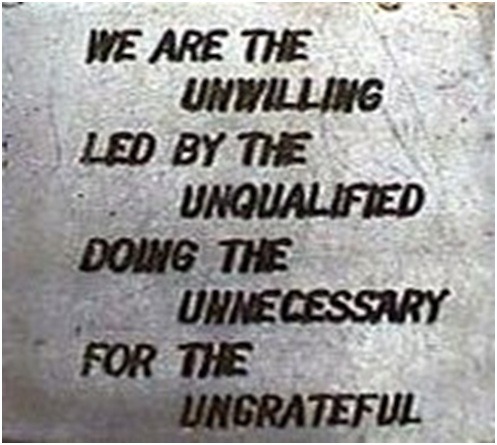

|

| Another favorite barracks poster |

So we self-medicated by drinking as much as possible, seeking the Spirit in spirits, trying futilely to drown our frustrations, our homesickness and loneliness and most of all our rage against the Body into which we had been forcefully incorporated.

We made sure to be properly hungover by the time we put on our ill-fitting and unsightly uniform every day in order to "protect our country." Not only did we enjoy inebriation and its accompanying numbness, but it seemed a kind of revenge to go to work while incompetent, if not downright incapacitated.

In this angry fraternity of machismo, conventional notions of worship were considered absurd and pathetic. Apparently, this isn't new. In Slaughterhouse-Five, set in the Battle of the Bulge, Vonnegut says this about Billy Pilgrim, a chaplain's assistant: he "had a meek faith in a loving Jesus which most soldiers found putrid."

|

| Baptist or Shinto? You make the call. |

On the one hand, I was on an island -- "Buddha's island" -- not dominated by people who called themselves Christians. On the other hand, I was separated from whatever spirituality Japan had to offer by living and working among resenters, dissenters, resisters and apostates.

Before I reflect further on this stage of my lifelong quest, I want to tell you about a young man who was determined to change the ethos of the barracks, i.e., to persuade us to abandon our sins and develop a meek faith in a loving Jesus.

You wanna guess how that worked out?

Before I reflect further on this stage of my lifelong quest, I want to tell you about a young man who was determined to change the ethos of the barracks, i.e., to persuade us to abandon our sins and develop a meek faith in a loving Jesus.

You wanna guess how that worked out?

No comments:

Post a Comment