"When the student is ready, a teacher will appear."

(The following is an anecdote my memory coughed up a few days ago when a sip of orange juice went down the wrong way. It is mostly factual and all true, and, during its telling, I make no effort to intrude or reflect or interject or give a moral lesson. That part comes after the story, so feel free to stick around for refreshments and reflections during the closing credits.)

Out of all the learning that flew about my high-school classrooms like so many wounded doves, not much of it attached itself to me. When it did, it came off before my daily shower. I only rented knowledge in high school, I didn't buy it. Why would I want to pay for something like a list of Paraguay's major exports anyway? Once I'd made my 76 on the test, I was all done with it.

In her own way, my senior English teacher Mrs. Damedesu* tried to distribute some worthwhile knowledge. Incidentally, she was the one who alerted our class to the existence of dirty biblical passages.

One day in class she asks me to step outside with her for a moment. She is a somewhat legendary teacher and I am just a teenager trying get through one more lousy year of high school, so this invitation unnerves me.

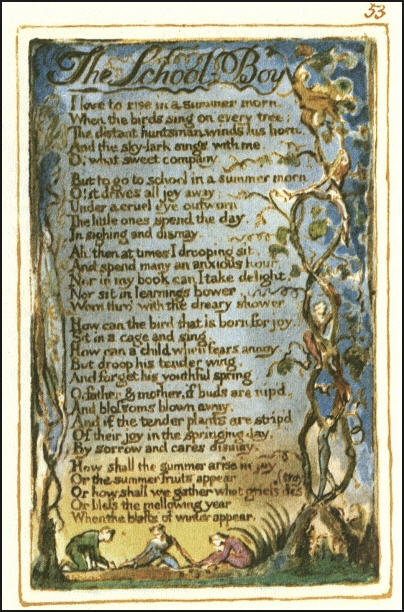

|

| What little school kid hasn't felt this? Can't read it? Google William Blake's "The School Boy." |

Once in the hall, I lean against the wall with my hands joined at the small of my back. Mrs. Damedesu anchors herself about four feet away from me, her arms crossed in the narrow opening between her sandbag bosom and her encroaching full-figured midsection.

She stares me down for an awkward moment, her head moving ever so slightly as if she were a gently tapped bobble-head doll.

"What's going on, Roy?"

"I don't know."

"Is it me? Do you have a problem with me?"

"No ma'am."

"Then why are you doing such poor work in my class? Sometimes you don't even turn anything in."

"I don't know. I guess that's just the best I can do."

"I don't believe that, Roy. Why aren't you applying yourself? What is going on with you?"

I think for a while, and give her the most honest answer I can come up with.

"I just don't care."

Mrs. Damedesu's head bobbles some more, a bespectacled beach ball floating on slightly troubled waters.

"You don't care."

"No ma'am. I just don't."

She takes a deep breath and looks at me in a way that suggests something profound is about to come out of her mouth.

"Roy, do you know what it means when you say 'I don't care'?"

"Well, I guess it means I don't care."

"That's where you're wrong, Roy. It really means you do care." Her forearms nudge her breasts up a bit as she strikes the pose of someone who has sealed the deal, won the debate, turn out the lights, close the curtains, party over, shut the door on your way out.

But I don't feel defeated, just confused, so much so that I ask her perhaps the most heartfelt question of my high-school career, maybe the only question I genuinely want answered: "Then how do I say I really don't care?"

"Just go back inside," she mutters in disgust, and opens the door. She has washed her hands of me, and that's fine with me.

*Not her real name, obviously

Blue Notes:

I found this story worth telling because it has one of my favorite issues in it: a complete inability to communicate -- two people who are unable to empathize with or read each other. How is a teacher, for example, supposed to communicate with this guy?

It never dawned on me that I was going to school to learn. I couldn't think of anything I wanted to know in any of my classes. I remember not giving a crap about the Hopi or Woodrow Wilson's 14 points or the difference between Tolstoy and Trotsky or the periodic table of elements or predicate nominatives.

Like most students, I didn't plan to grow up to be a teacher, so why should I care about all the crap embedded in boring, dusty textbooks?

It was all just a big load of horse poop as far as I was concerned. One crappy day followed another and those crappy days formed a crummy trail of crumbs that led to an induction center and then to the rice paddies. So I'd be sitting in class thinking, "Wait. I have to listen to my teacher talk about transcendentalism and I have to die? Well, that stinks."

But I wasn't even good at showing off my indifference or contempt. Mrs. Damedesu's classroom doubled as a language lab, so we sat at these little tables with dividers on each side and soundproof glass on the front. One day to demonstrate how little of a shit I gave about whatever Mrs. Wiatt was talking about, I pushed my chair back a bit and put my feet up on the table. I wasn't quite comfortable, so I used my feet to shove my chair farther back.

In so doing, my chair tipped over, sending my feet up into the air, my butt to the floor, my head banging into the soundproof glass behind me. First, the class went quiet and then, my classmates, seeing that no one of any great importance had been injured, giggled softly, while Mrs. Damedesu gave me the old "are you quite finished with your shenanigans" scowl, and I pulled my sore butt, bruised head and red face back into a normal sitting position.

Now let's move to the other side of the non-conversation depicted above.

It's very possible that Mrs. Damedesu loved her profession, felt called to it, just as I felt six years after surviving her class.

Maybe she came to work every day hoping to bring an understanding of and appreciation for the great early writings in English, beginning with Beowulf, to the young residents of rural north Florida, aka, the Last Place on Earth.

Such cultural awareness could help us pursue the American Dream of having a better life than our parents. An admirable mission, one that would add meaning to the life Mrs. Damedesu would live out in a little "postage stamp of land" mostly ignored by the rest of the world.

To help us on our way, she had us memorize the first 15 lines of the General Prologue of The Canterbury Tales, and I grew up to make my students memorize poetry to try and rinse the advertising jingles out of their battered brains. Maybe she inspired me to do that, even if I didn't care.

Just now, I remember she taught us the words "baleful" and "palpable," both, I think, coming from Milton. But I also remember she made us listen to an entire recording, on vinyl, of Shaw's Pygmalion. Oh, that was boring as snot.

Surely she was frustrated, like all teachers, that we weren't all getting it, that she could lead us to water, but not make us thirsty. And she looks out and sees kids like me with their feet up on the table while she's reciting, with great feeling, but with little music, "Let me not to the marriage of true minds / Admit impediments."

And maybe she knows that kids like me actually have a gift inside we're either unaware of or are purposely ignoring. She can see it. This candle, its lighting baffled by a breeze, wanting to break through the darkness. If only she could talk to that kid.

She says to herself, "Maybe one day I'll have a talk with him in the hall, like my teacher did to me, after which everything changed, and instead of skipping college and becoming a secretary at Uncle Fred's Feed Store, I went out into the world and learned the wonders of language and I learned to love learning. Even now, my heart leaps up to think of it."

And maybe she looked out at us again, with our distractions and our stony indifference, so many of us, and picked one, and with a little glimmer of hope, thinks, "Oh, but so few are chosen. Perhaps I can save this one. Yes, I will do that."

"Roy, could you step outside with me for a moment?"

No comments:

Post a Comment