1. What were race relations like in that setting? In the tobacco fields of pre-Civil Rights Madison County, blacks and whites worked side by side. My intent in this piece is to relay honestly, accurately and without commentary only what I saw from my point of view, i.e., that of a fairly ignorant young white boy. I will neither dress up nor sensationalize what I saw. As has always been the case in my Memoir postings, my memory speaks, and I record it.

|

| Eva Marie Saint blows out Cary Grant's match in "North by Northwest." She insists! |

2. Did cultivating, harvesting and curing a plant that kills people create a moral dilemma? No. Back then, cigarettes were used in movies as status (and often Freudian) symbols, and it was not altogether clear, especially to R.J. Reynolds and Phillip Morris, that they were related to lung cancer and heart disease.

If a friend approached you, it was polite to offer her a cigarette. If you were a sophisticated smoker, that cigarette might come out of a silver case, inscribed with your initials.

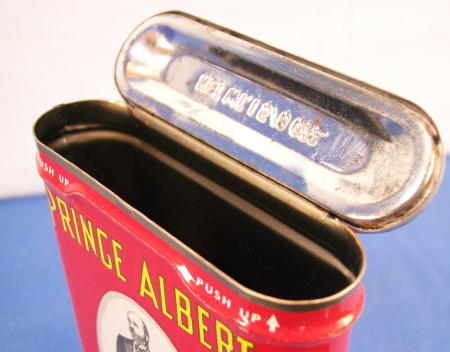

For Christmas, we always got my granddaddy a box full of Prince Albert smoking tobacco in those cool red sort of flask-shaped tin cans. We were telling him "We know what you love," not "Hurry up and die."

In short, about everyone smoked as if they were Europeans. Taking the cellophane wrap off a fresh box of weeds, taking one of the little cylinders out and tamping it before igniting it with a shiny Zippo was as common then as being rude with cellphones is today.

Okay, now here is some necessary background -- which seasoned tobacco workers are free to skip over -- to help this otherwise lucid narrative make sense:

If a friend approached you, it was polite to offer her a cigarette. If you were a sophisticated smoker, that cigarette might come out of a silver case, inscribed with your initials.

| Cigarette play in "Now, Voyager" |

In short, about everyone smoked as if they were Europeans. Taking the cellophane wrap off a fresh box of weeds, taking one of the little cylinders out and tamping it before igniting it with a shiny Zippo was as common then as being rude with cellphones is today.

Okay, now here is some necessary background -- which seasoned tobacco workers are free to skip over -- to help this otherwise lucid narrative make sense:

|

| Add rolling papers and matches and you got yourself a lifelong "friend." |

When I began working in tobacco in north Florida in the 1950s, it was harvested like this: A crew of five or six males, usually boys, both black and white, in their mid to late teens, but occasionally including a black adult male or two, went out into the tobacco field riding in a wood-frame sled covered in layers of burlap and pulled either by a horse, a mule, or, if the farmer was high-tone, a tractor.

|

| A tobacco field |

These guys were the “croppers,” and each of them would start in on a row of tobacco and crop the ripe leaves, typically the bottom three or four on the stalk, starting to show a little yellow. When they had cropped as many leaves as they could carry under their arm, they’d dump them, stems facing outward, into the sled. When the sled was full, it was towed back to the barn, and the horse-rider or tractor-driver emptied it onto long tables, either under the tin awning of the barn or in the shade of oak trees.

Here young people of either sex or race and adult women of either race (called "handers") would grab three and four leaves at a time and hand them to a “stringer,” an adult woman of either race, who attached them with twine to a 4-foot-long cube-shaped stick which was resting on a support called a horse.

|

| A poor guy hanging tobacco in a barn where it'll cook. |

A guy would have to stand on rails, one foot on each, a little over a yard apart, reach down and take the stick from someone on the floor of the barn, then either place it on the rail above him or hand it to another hanger on an even higher set of rails. This was dangerous back-breaking work that required athleticism and great balance. Only the varsity croppers were called on to be hangers.

To review the roles quickly: handers (young, weak or inexperienced), stringers (veteran females), full-stick remover (pre-teen of either race), croppers (robust young men of either race and grown-up black men), horse-rider or tractor-driver (usually an adult, sometimes an overseer, occasionally just one of the croppers) and hangers (athletic croppers with no back problems).

I first made money working in tobacco when I was 8. The back part of our old house was used by a black sharecropper as a place to take cured tobacco off the stick, then arrange it in doughnut-shaped piles and tie it up in a huge burlap sheet before tossing it on the back of a truck to be taken to Madison for auctioning. So, yes, the back part of my home was a small tobacco warehouse.

The black sharecropper was Nat Thomas (called Nay-THAN by his wife Lula), and he sharecropped with my Granddaddy Young, my mom’s dad. And the tobacco in my house came freshly cooked from the barn across the street. That same barn burnt down twice in a period of about eight years. (Once when the barn burnt, my dad was working on the transmission of our pathetic yellow English Ford Consul when the conflagration broke out and, even with a bad back prone to slipped discs, he picked up the transmission and rushed it like a heavy baby across the road to safety.)

Nat had neither telephone nor e-mail, so someone had to drive up to his house and tell him his barn burnt down or wait for him to drive over and see it for himself.

So one summer day I was hanging around in the back of the house talking to Lula, a short, thin woman who had the coloring of movie Indians, always in a straw hat and a loose fitting dress. I saw some of the stuff she was doing, so I started doing it because, I don’t know, I liked to feel productive: things like sweeping up loose pieces of tobacco leaves or handing her the next stick of tobacco to de-string. I must have done this all afternoon, so when Nat came by to pick her up, she took on over (i.e., exaggerated) what a big help I’d been to her.

Nat was a huge man, with a broad face, high cheek bones, piercing dark-yellow eyes, with a wide mouth and big lips that stretched practically across his entire face. After Lula bragged on me, he cocked his head and said, “Sho nuff?” Then he fished around in the pockets of his khaki work pants and handed me a fifty-cent piece. “Here’s ya some money to buy ya some can’y wit.”

So in 1958, a black man who kept his tobacco in the back of my house gave me my first salary. I’m pretty sure I wasn’t allowed to buy “can’y” wit it.

That's how it all started for me. In my next tobacco post, I'll take you out in the fields, so hydrate now!

The carbon is "initiated" when it is treated with oxygen, which opens up a large number of small pores to pull in and adsorb chemicals. air purifier smoke

ReplyDeleteFor making cigars, tobacco is grown all around the world, from Poland to South Africa, from Argentina to Canada and, westbound, from Philippines to Mexico. But cigar tobaccos are mainly grown in the intertropical areas.

ReplyDeleteiqos cigarette buy

My father was a young boy in the '20s and 30s and he pulled a sled tobacco sled with the horse. He also was trapped in a tobacco smokehouse by one of his cousins. Thankfully his cousin's mother realized what was going on and got him out of there. It was tough living back then. I don't know how they did it but they did it.

ReplyDelete