I’m sitting

in a local coffee shop waging a pleasurable war with Cormac McCarthy’s prose in

his 1979 novel Suttree, and I’m also

trying to keep my coffee and croissant from coming back up as his prose

delivers images that disturb all five of my senses. As usual, McCarthy builds

his masterpieces out of mud, blood, pig guts, sewage, gout and slag (two of his

favorites) and worse.

|

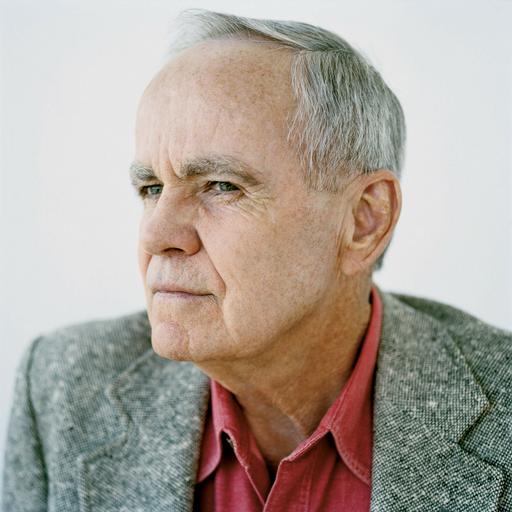

| Cormac McCarthy |

A plot synopsis isn't going to help much, but I will tell you that Cornelius "Buddy" Suttree has for some reason left his family to live among the river people, scratching out a living selling fish. He is deep into alcoholism, and the company he keeps make Gomer Pyle, Jethro Bodine and Ernest T. Bass look like models of intellect and refinement.

Out of

habit, I think about how I would teach such a book, and I quickly realize that,

for many reasons, parents and school officials would label it inappropriate for

teenaged readers, the same parents and administrators who have never walked

down the halls of a typical middle school and heard language inappropriate for

hardened criminals and combat veterans.

And Suttree could not be taught at a university without a list of trigger warnings that would fill an old-fashioned phonebook. There’s something in there to offend everyone, mainly because it tells the truth.

Furthermore,

on both the high-school and university level, students would find McCarthy’s

language impenetrable. I know of no English word sufficient to describe his

word choice. I am a life-long reader with a small truck full of degrees in

English, and I’m lucky to get through a page without having to sneak a peek at

dictionary.com or wrack my brain to decipher in context the meaning of an alien

configuration of letters. Or, more likely, just take the sentence’s dense, obscure

but evocative poetry on faith and enjoy its strangeness, as a puzzle to be

marveled at.

For these

reasons, 96% of students of any level would stop reading and retreat to the all-embracing

but narrow-sighted, undiscerning, oversimplified arms of the whore Spark Notes

with its seductive air of academicese.

But are those reasons sufficient to back away from such books as Suttree? No.

For one thing, some public schools still teach Shakespeare, even though at my old school most kids were all done with the Bard after they clawed their way through Julius Caesar, both the play and the entirety of the Marlon Brando movie, in tenth grade.

Still,

decades ago, progressive, idealistic teaching gurus argued that we were ruining

Shakespeare for students by forcing him on them before they had the maturity to

understand him. We were teaching them only that Shakespeare was difficult, that he did

not reward the time they invested with any immediate pleasure, with few if any

shocks of recognition or startling insights. Therefore, to the students, at least, he was boring.

Years later,

these same kids would grow up and attend cocktail parties where, while sipping

a Manhattan, they would embarrass themselves by saying “I couldn’t get into

Shakespeare. That Old English was just too hard to read.”

Hwaet?!

(Are we

supposed to wait for human beings to mature into an understanding of Shakespeare?

As a great critic once observed, “We all misunderstand Shakespeare in our own

way.”)

In short, some

schools still teach Shakespeare even though most students have no clue what’s

happening in his own language.

So despite his obscurity, maybe we should consider tossing McCarthy into the mix. He is, after all, considered by

many critics and fellow writers to be among America’s very best living

novelists (unless he died last night). It is worth giving students a chance to

see why that’s the case.

This, of

course, would force teachers to stop thinking about those Godforsaken useless

Marzano teacher-evaluation indicators long enough to pick up a new and

challenging novel and figure out ways, probably not including infantile Kagan exercises,

to help students see McCarthy’s brilliant achievement.

For all the

mysteriousness and Otherness of Suttree, there are intelligible things to be

said about how McCarthy uses literary techniques, for example, to make us feel like

our feet are stuck in mud, as are the characters’, or like we are trying to

escape danger in a nightmare, but are paralyzed. And how does McCarthy use his

syntax to make time itself sluggish, to bind a reader to a particular page well

past the usual 2-minute rule, well past the time the reader wants to spend there,

because it is not a comfortable place. How does he hypnotize the reader into

lingering over passages he would otherwise skim?

This stuff

doesn’t just happen. It would be productive for a teacher to think through McCarthy's choices and their effects as he writes and revises. It would keep the teacher from explaining for the eighty-third time

why Harper Lee decided to have Atticus Finch man up and shoot that damn rabid

dog.

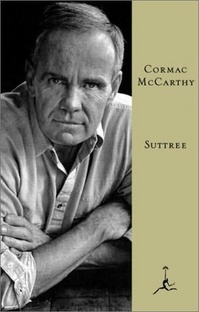

|

| Atticus during his non-racist, dog-killing stage |

Aside from

McCarthy’s dazzling technique, his works, esp. Suttree, contain cultural data which

educators now claim to hold so dear. His depiction of the very poor (about which

I’ll say more in a future post) would teach kids a whole lot they should know

about the Land of Opportunity and the conditions of the euphemistically labeled

“less fortunate.” I’ve not seen such a muted, unsentimental, non didactic, non whiny, deadpanned depiction of the hopeless condition and necessarily flexible

morality of the undeserving poor since Hansel and Gretel’s mom tried to starve

them, and her alter-ego in the forest tried to eat them.

Admittedly,

students would not read all of Suttree,

in fact, they would read very little of it. Happily, they'd be unlikely to reach the parts that would disturb their parents and/or youth ministers. But in art history, they can’t see

all of the dabs and mini-strokes Van Gogh used to create “Starry Night” either, but

the teacher helps them see enough, and if students have an inquiring mind,

they have the rest of their lives to fill in the gaps.

Two more

arguments for teaching masterworks that may be considered unreadable and inappropriate:

First, I

learned long ago that few students, even in the varsity course Advanced

Placement Literature, actually read the assigned books. For a while, I tried down-sizing

and dumb-downing to put the works closer to their reading sweet spot, but that

made me feel cheap, and besides, they didn’t read those either.

So I decided if

they weren’t going to read books, they might as well not read great books.

This

led me, for example, to John Fowles’ French Lieutenant’s Woman, and it became

the favorite of a handful of my young scholars and exposed all of them to some thoughtful discussions of a postmodern attempt to re-see and rethink the

Victorians’ struggle with new science and old religion.

Second, you, dear reader, should stroll through a typical public high school’s English department

book-storage room. In most cases, you’d learn that Harper Lee was the last

great American novelist, and that all the books you and your parents read in

high school are still sitting on dusty shelves, some of them waiting to be shoved into students’

dusty lockers. The books you were assigned decades ago continue to be "appropriate reading," meaning the characters

will not, for the most part, have genitalia, which seems to me to be misleading

for teen readers, nor will there be scenes that stir up legitimate but uncomfortable questions about religion and politics, neither of which teachers are supposed to weigh in on.

Their blandness will confirm students' belief that reading out of the Harry Potter and YA zone is a joyless, wearisome endeavor.

Lodged back

there on some forgotten upper shelf in a corner, waiting to be hauled off to the county office and placed in an oven set at roughly 451 degrees Fahrenheit, will be retired copies

of Scarlet Letter, Moby Dick, Great Expectations, Tess of the d’Urbervilles,

Huckleberry Finn, Jane Eyre, Sound and the Fury, White Noise and other ghosts of another time.

The newer

books in the storage room will be rightfully acquired to expose some students

to different cultures and rightfully help others feel represented by their own

culture’s art, but they are not necessarily there to show how writers of yore spun their yarns in beautiful prose or how more recent ones re- imagine their genre, testing its limits to adapt it to an ever-changing, ever more complex reality.

So. The magic of writing has just now transformed me from a happily retired man, happily sipping a terrific cup of coffee, while happily devouring another great book that teaching allowed no time for, into a sad old recluse in a high tower, staring out a window revealing a once lush literary landscape shriveling and wilting, its magic exorcised daily, that old, old wonderful world turning wasteland barren, a father and his son sifting for something of value among the ruins.

Every high school student should be required to read McCarthy's The Road just in case they grow up to be Republican presidential candidates.

ReplyDeleteRichard, I'm so unaccustomed to getting comments, I failed to respond to yours. I apologize. I also agree with what you said. Not to generalize or anything, but Republicans could learn a lot from reading several of McCarthy's novels.

Delete