You wanted from this life, even so?

I did.

And what did you want?

To call myself beloved, to feel myself

Beloved on the earth."

--"Late Fragment," Raymond Carver

The lines above were written near the end of Raymond Carver's brief life (he died at 50 in 1988), and were probably addressed primarily to his wife at the time, Tess Gallagher. But he was beloved by many, many more people in those final days, and I certainly count myself among them. When people come up to me on the streets of Oviedo and ask, "What writers can you credit for improving your life on the earth?" Carver's name comes quickly to mind.

|

| Ray |

I have actually said, both to myself while driving and aloud in front of people, "My life has been better because Ray Carver lived and wrote."

It hasn't always been that way. When I first heard about him and his so-called school of literary minimalism, which also included Bret Easton Ellis, Grace Paley, Bobbie Ann Mason, Mary Robison, Tobias Wolff and Richard Ford, I didn't like him at all.

Sure, I hadn't read him yet, but well-known literary critics and reviewers made both Carver and his reticent gang sound awful. Some said, for example, that he was just Hemingway without the lions; others complained he only wrote "inside the house" stories that start at nowhere and end there, too, telling us nothing about the complexities of society or the great world as a whole.

Carver's writing, they argued, is sub-journalistic, lacking any musical qualities, completely eschewing diverse syntax, metaphorical language, meaning-laden symbols and allusions. Critics not only provided the "minimalist" label, they also generated such colorfully derisive names as K-Mart Realism, Shopping Mall Realism, Literature Lite, Trailer-Trash Lit and Hick Chic.

|

| Jessica Hardy says this is the proper response when people say bad things about Ray. |

For a while, I took their word for it. During my first sabbatical, however, I had some extra time on my hands and decided, what the hey, let's see how this loser sounds. I started, oddly, with "A Small Good Thing," and when I finished, I felt like someone had kicked me in the stomach (more about that story later). Then I read "They're Not Your Husband" and "Nobody Said Anything," and I felt like someone had kicked me in the stomach two more times.

I started teaching Ray (really, I feel comfortable calling him Ray -- the only other writer I'm on a first-name basis with is Tim) in the early '90s, and found that a huge percentage of my students loved him, too. I have evidence to prove it: No literary text was more often stolen during my 15-year tenure at Oviedo High than Ray's posthumously published collection Where I'm Calling From. Roughly 45 of the original 60 never found their way back home, even though I'm sure I was very thorough in having the kids sign them back in.

What did they like about him? What drew my students to Carver's mostly spare, low-affect, deadpanned, inconclusive yarns about luckless, obscure, inarticulate, uneducated, often alcoholic Americans? What follows are some typical responses to those questions. Please note how my former students' commentary frequently addresses the major complaints of Ray's detractors. Also, feel free to envy the quality of students I was privileged to teach, both at Oviedo High and Rollins College:

Elise Carlson: "Carver was tough to take at first, since his writing is so stark, but I actually grew to love it (along with Flannery O'Connor's) for its simplicity in the face of complex issues. Carver skillfully condenses large ideas into small stories with a directness that hits home."

Colleen O'Kennedy: "I especially admire his ability to convey the more melancholic aspects of human experience, whether it is loneliness or entrapment in 'The Student's Wife' or discontentment in 'Neighbors.' Carver almost always chooses to illustrate some emotion or experience people are generally ashamed of. Perhaps that is why [some] tend not to like his work -- because his stories confront the parts of their existence they would rather not acknowledge or explore. [Like the student's wife], people do not want to be left alone to think about their shortcomings, and they have a tendency to close doors that only lead to more doors. The emotional resonance and poignancy of Carver's stories may be overwhelming -- I was troubled, almost inordinately so, by the wife's desperation in 'Student's Wife' and the couple's perversion in 'Neighbors.'" Colleen concludes by suggesting that Carver's writing may well "unsettle many readers who attempt to engage it."

Chris Moskal noted the great depth in Carver's seemingly flat stories and added "he drops you in to a place and time in [his characters'] lives and only gives you a glimpse, but it's always exactly the amount of time you need."

Cameron Nix: "I found Mr. Carver's work to be wonderful in the most unexpected way. I typically associate good writing with lush detail and rich backstories. However, he did something drastically different, using minimal detail and simply dropping you into the story, rather than setting the scene, leaving the creation of the world to the mind of the reader. I also appreciate the melancholy atmosphere of his stories. They are a welcome change . . . from the 'happily-every-afters' most writers lean toward."

Ciara Barone: "Carver is just about the best [writer] I've ever been exposed to. His style is very unique in the sense that he doesn't dress up his descriptions. . . . I've taken several creative writing courses and they've all taught me to over describe. I have a sort of love-hate relationship with the open-endedness of the stories, but I think it's really masterful to create something that can be interpreted in a variety of ways. Carver actually made me want to write short stories."

Taylor Hughes: "While critics are eager to slap 'blue collar' or 'minimalist' on Carver's collections, . . . he denied those labels and therefore shrugged off the attention of the label-hunting students studying his craft long after his death. I find that critics and scholars are made uncomfortable by disabilities, by obesity, by intimacy. To (inevitably) identify with these ideas is to bring to the surface a reader's own shortcomings and prejudices, which are more easily, and more comfortably, left to collect dust in the sitting-room bookshelf."

Adam Loewy: "Carver takes those simple [issues] we don't want to talk about and writes about them in a way that you can either accept the issues 'as is' or think more deeply about what the characters might be going through. As a dad, I've picked up 'Bicycles, Muscles, Cigarettes' quite a bit lately!"

Claire Volheim: "I always thought he could use such simple language to weave something much more profound. His stories always stick with me -- there's a big 'wow' every time I put the book down."

|

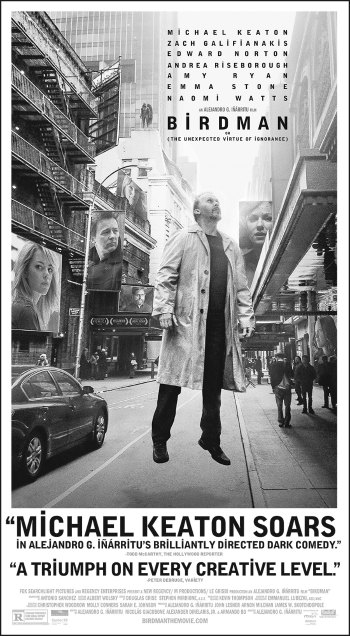

| In "Birdman," Keaton's character attempts to stage a Carver story. |

A big thanks to all my student contributors. In future posts, I'll take a more careful look at several of the Man's stories.

No comments:

Post a Comment