Even though I'm retired, my brain is still hanging on for a while, still grudgingly willing to do some problem solving and make a few connections here and there, as long as it gets a little buzz out of the whole deal.

I got in this quandary due to a friend strongly suggesting I read Cormac McCarthy's Blood Meridian. I raced home, read half of it, put it down, picked up McCarthy's No Country for Old Men and, even though I had already seen the movie, was stunned by its profundity and power.

For a few days, the thing just stayed in my head and dared me to read another book. It's just so troubling and, well, beautiful. I could make a living writing jacket blurbs for this musky jewel. Then I started pondering the title, where it came from, what it might mean; and I started comparing it to more traditional views of the West. Intriguing! Puzzling! And here are the pieces:

McCarthy's No Country for Old Men (2005), obviously; William Butler Yeats's poem called "Sailing to Byzantium" (1927); a John Ford Western, starring John Wayne, called The Searchers (1956); and finally the Coen brothers' film version of McCarthy's novel in 2007.

First, I'll attempt to interpret Yeats's poem as seen through the eyes of a moderately intelligent, somewhat -- but not fully -- enlightened reader who read the poem probably three times when he was in grad school in 1978, then once more a few minutes ago.

I make that qualification because I know there are at least a dozen Yeats scholars, doctoral students and people who have bumper stickers featuring characters far, far removed from life as we know it here on earth who are eager to pounce on any interpretation that doesn't consider Yeats's dalliance with the occult, his relationship to Dark Masters and Mistresses such as Madame Blavatsky, Alistair Crowley, Jimmy Page, Swedenborg, Paracelsus, Jakob Boehme and the Lucky Charms leprechaun.

I know all about that, and about his preoccupation with the 1000-year cycles, and the widening gyre and various Second Comings and Goings and automatic script dictated from beyond to his poor wife George.

So back off and let a brother talk about the poem just as a poem so I can figure out what it has to do with the rest of these puzzle pieces!

Here's the first sentence: "That is no country for old men." Yes, the poem begins with a definite article ("That"), a part of speech that supposedly points toward something specific the reader already knows. But we don't know. What is no country for old men? That's a big question. You could write an entire book on . . . oh, wait. McCarthy already has.

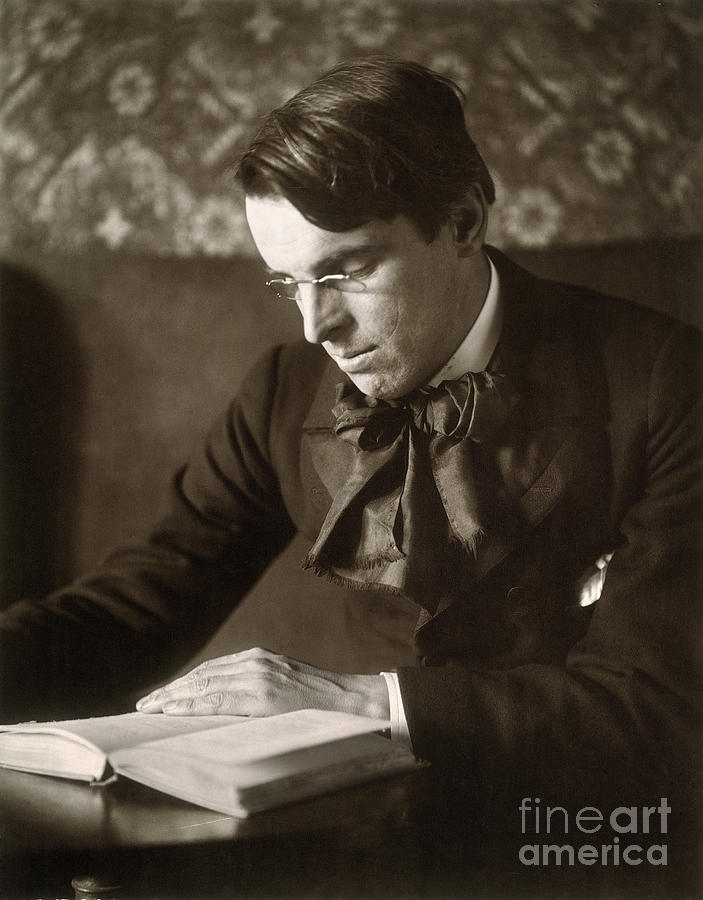

|

| Yeats as an old man, a paltry thing |

Yeats soon gives a reasonably clear answer to the question, followed by an even more specific description of the country the narrator longs for. "That" country is probably quite similar to a Nicki Minaj or Lana Del Rey video: Young lovers making out, birds singing in the trees, salmon and mackerel making a guest appearance for purely symbolic purposes, all of them part of "dying generations" and all caught in "sensual music." An old man would simply want those kids -- and the fish -- off his lawn.

|

| Yeats as a young man, like the lovers in his poem |

The second stanza describes an old man, then tells us he doesn't have to be that way, thus parting the curtains for a peek at the country that is for old men: "An aged man is but a paltry thing, / A tattered coat upon a stick, unless / Soul clap its hands and sing, and louder sing / For every tatter in its mortal dress."

This soul-singing leads Yeats, in the third stanza, to an invocation: "O sages standing in God's holy fire / . . . / Come from the holy fire . . . / And be the singing-masters of my soul. / Consume my heart away; sick with desire / And fastened to a dying animal, / It knows not what it is." This line is followed by a reference to the "holy city of Byzantium," but given my backwoods, pseudo-scholar, rusted New Critic persona, how could I possibly know what that means at this point in the poem?

Sounds like the narrator (probably Yeats, don't you think? He would've been 62 at the time) longs for ageless Wisdom to spin out of the holy fire and teach his soul its endless song and take possession of and/or devour his old heart confused by a desire that can no longer be fulfilled by performance.

The stanza ends with Yeats asking the sages to "gather [him] / Into the artifice of eternity." In the final stanza, Yeats elaborates on this concept, and here's a sampling: "Once out of nature I shall never take / My bodily form from any natural thing, / But [take] such a form as Grecian goldsmiths make / Of hammered gold and gold enameling." And once out of nature, he may find himself "set upon a golden bough to sing / To lords and ladies of Byzantium / Of what is past, or passing, or to come."

The Byzantium to which Yeats sails now seems to stand for that which neither fades nor dies, a place where young lovers (unlike the ones in the first stanza) can never kiss, but will love forever, will be "for ever panting, and for ever young," a place, in short, much like Keats's eternal artifice, the Urn, if not exactly like it.

So what country is not for old men? The one in which all life is busy being born and busy dying, where young love is heartrendingly transitory, and all of magnificent nature with its singing and swimming quickly comes and goes.

And the country that is for old men? A place of divine wisdom where we leave our dying, fleshly animal selves behind, where we are transformed into golden Greek art, where our souls sing "Of what is past, or passing, or to come."

|

| Yeats in a world where nothing changes |

We'll be back after these messages to speculate on why McCarthy took his title from this poem. Sure, we could probably find that answer in an interview, but that would be too easy and not nearly as much fun. Meanwhile, here's Yeats's entire poem for your reading pleasure: "Sailing to Byantium"

No comments:

Post a Comment